Motives for giving

Project descriptions, links to papers and presentation slides

Optimal Incentives to Give

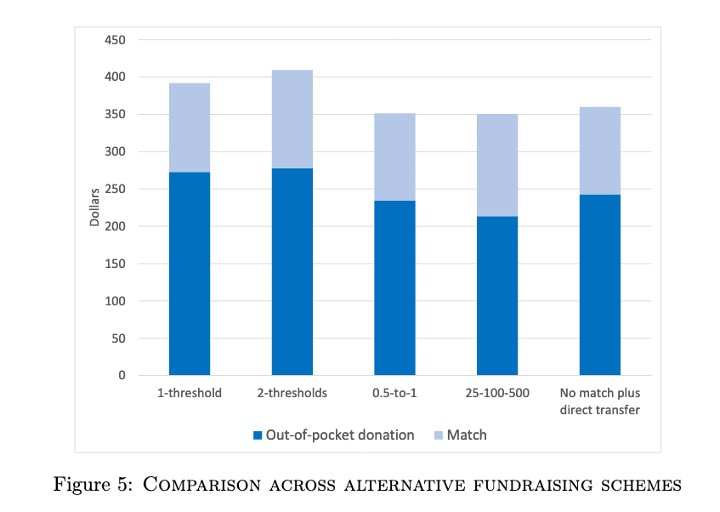

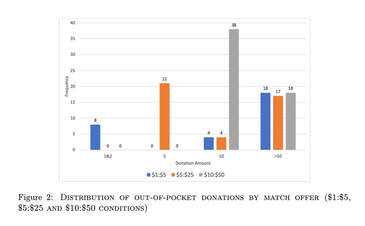

Charities often use dollar-for-dollar matching in their fundraising campaigns, but it is not clear if this is the most effective. We explore an alternative matching incentive that provides a fixed match if a donation meets or exceeds a threshold amount (e.g. "give at least $25 and the charity receives a $25 match"). A large-scale field experiment, involving 26 charities and over 112,000 individuals, is conducted with randomly-assigned threshold match amounts to potential donors. We find that out "best-guess" thresholds, informed by consultation with fundraising experts, were set too low to be effective at raising out-of-pocket donations. Thresholds should be set much higher, i.e. around $1,250. In a two-year, follow-up study, this high threshold scheme increased out-of-pocket donations for the charities by 5.4%. Our findings highlight the importance of testing different matching schemes and using experiments to explore out-of-sample alternatives that might be more effective. Link to paper Slides from Economic Science Association Global meetings plenary, "Do charities know what triggers donations?", 2021, (includes summary of this research and giving advice to charities) Castillo, Marco and Ragan Petrie, 2021, "Optimal Incentives to Give," Working paper |